The Sigh

- Musical Analysis Section

- Audio Recordings Section

- Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

- Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

- Carlisle - Gerald Finzi: A performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and

- Denning - A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

- Rogers - A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

- Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

- John Keston - Two Gentlemen from Wessex, The Relationship of Thomas Hardy's Poetry to Gerald Finzi's Music

Poet: Thomas Hardy

Date of poem: (undated)

Publication date: In the collection: Time's Laughingstocks (1909)

Publisher: Macmillan Publishing Company

Collection: Time’s Laughingstocks published in 1909

History of Poem: Martin Seymour-Smith makes the following comments about The Sigh: "This could be a recollection of Emma, but it is more likely to be related to his experience with Florence (Dugdale, later his second wife), who might have sighed for Hyatt (a former suitor), or just out of self-pity from which she habitually suffered. The poem, within its brief compass, seems to condense the whole experience: Such are the illusions of love, which changes rapidly."

(Seymour-Smith, 719)

Poem

| 1 | LITTLE head against my shoulder, | a |

| 2 | Shy at first, then somewhat bolder, | a |

| 3 | And up-eyed; | b |

| 4 | Till she, with a timid quaver, | c |

| 5 | Yielded to the kiss I gave her; | c |

| 6 | But, she sighed. | b |

| 7 | That there mingled with her feeling | d |

| 8 | Some sad thought she was concealing | d |

| 9 | It implied. | b |

| 10 | - Not that she had ceased to love me, | e |

| 11 | None on earth she set above me; | e |

| 12 | But she sighed. | b |

| 13 | She could not disguise a passion, | f |

| 14 | Dread, or doubt, in weakest fashion | f |

| 15 | If she tried: | b |

| 16 | Nothing seemed to hold us sundered, | g |

| 17 | Hearts were victors; so I wondered | g |

| 18 | Why she sighed. | b |

| 19 | Afterwards I knew her throughly, | h |

| 20 | And she loved me staunchly, truly, | h |

| 21 | Till she died; | b |

| 22 | But she never made confession | i |

| 23 | Why, at that first sweet concession, | i |

| 24 | She had sighed. | b |

| 25 | It was in our May, remember; | j |

| 26 | And though now I near November, | j |

| 27 | And abide | b |

| 28 | Till my appointed change, unfretting, | k |

| 29 | Sometimes I sit half regretting | k |

| 30 | That she sighed. | b |

(Hardy, 227-8) |

||

Content/Meaning of the Poem:

1st stanza embraces the tender beginnings of a relationship and yet a seed of suspicion is planted in the last line.

2nd stanza the speaker attempts to analyze the sigh that ended the first stanza. He attempts to bolster his opinion as to her devotion by stating that she put no one higher than he, but yet, she sighed when he first kissed her.

3rd stanza speaks of a strong relationship between the speaker and his beloved. He again attempts to deny that she could love anyone more than he, and yet the sigh continues to nag at him.

4th stanza speaks of her love for the speaker until she died. The speaker regrets never learning why she sighed.

5th stanza uses the metaphorical image of there love beginning in the spring of their lives and how now the speaker is nearing the winter or end of his own life without any worries, but yet, he still ponders why his beloved sighed.

For additional comments as to possible meaning of the text please refer to: Content - Van der Watt and Comments on the poem - Carlisle.

James Osler Bailey writes with regards to the twenty-eighth line of the poem: "One phrase, "Till my appointed change," echoes Job 14:14, ". . . all the days of my appointed time will I wait, till my change come.""

(Bailey, 217)

Speaker: Probably the author himself but as to whom he was recalling there are a few candidates.

Setting: Nothing specific but one can assume from the text that the speaker is pondering a life of memories that he had with a beloved one.

Purpose: To remind one to communicate with loved ones and also to not allow feelings to fester.

Idea or theme: Regret

Style: The style of the poem is lyrical.

Form: Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt writes in his dissertation about the form of the poem: "The poem consists of five sestets with a shortened third and sixth line in each stanza. The rhyme scheme is aabccb ddbeeb etc. The shortened lines rhyme throughout and the final line of each stanza becomes a varied refrain. The metre is mainly trochaic with some minor variation."

(Van der Watt, 127)

Synthesis: The poem is chocked full of regret and suspicion and yet the speaker was obviously committed deeply to the relationship. One wonders if the sigh is what compelled the speaker to continue to pursue the relationship almost as if the beloved held him in ransom with the sigh. The last stanza uses the metaphor of "November" and "appointed change" to show the speaker is nearing the end of his life of regret for never learning why his beloved sighed. If one considers the poem autobiographical of Hardy and one thinks of his relationship between himself and Emma one could easily make the leap to his regret that he and Emma had grown apart. One could also ponder the thought of Emma wanting a different life path than the one Hardy had chosen and perhaps Hardy regretted not giving in to her wants and desires. One could also ponder the question as to whether or not Hardy wants the reader to consider whether or not one could ever truly know another's heart completely. Lastly, this poem could be a test of faith which it seems the speaker is found lacking.

Published comments about the poem: James Osler Bailey offers the following comments about the poem: "THE SIGH is a dainty poem that critics have analyzed variously. Even in the moment of yielding her first kiss, the poem suggests, a woman may pine secretly for another love, "a commonplace of present-day literature. One has only to think of Proust's large statement of the impossibility of knowing, possessing, and uniting with the person loved - an impossibility arising from the fact that each individual . . . creates and inhabits his own universe." (Perkins, 147-8) Hogan finds the poem humourous: "Throughout each stanza the perturbed lover reassures himself of her sincerity, only to return amusingly at each final line to the most delicate of doubts." (Hogan, 219) Hardy expressed the idea of the poem in Under the Greenwood Tree: when Fancy Day seems fickle and Dick Dewy is despondent, his father Reuben says: "Now, Dick, this is how a maid is. She'll swear she's dying for thee, and she will die for thee; but she'll fling a look over t'other shoulder at another young feller, though never leaving off dying for thee just the same." (Part the Second, Chapter VIII.)" (Bailey, 217)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses

- Collection of 94 poems written by Thomas Hardy.

- Published in December of 1909 by Macmillan and Company.

- Poems were written over a period of 40 years.

F. B. Pinion categorizes the poems as generally somber in tone with some having a more light-hearted nature. (Pinion, 64)

Edmund Gosse wrote on Dec. 7, 1909, "how poignantly sad! What makes you take such a hopelessly gloomy view of existence?" (Pinion, 64)

"A reviewer for the Daily News complained that, throughout the volume, 'the outlook [is] that of disillusion and despair." (Wright, 313)

Hardy responded to the reviewer by saying more than half do not fit the description.

(Wright, 313)

Gerald Finzi set the following poems within this collection:

- 1967 [titled by Finzi as: In five-score summers!] (I Said To Love)

- Former Beauties (A Young Man's Exhortation)

- He Abjures Love (Before and After Summer)

- In The Mind's Eye (Before and After Summer)

- I Say, 'I'll Seek Her' (Oh Fair To See)

- Let Me Enjoy (Till Earth Outwears)

- The Market Girl (Till Earth Outwears)

- The Sigh (A Young Man's Exhortation)

Helpful Links:

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Musical Analysis

Composition date: 1928 (Banfield, 144)

Publication date: Copyright 1933 by Oxford University Press, London.

Copyright © assigned 1957 to Boosey & Co. Ltd. (Finzi, 154)

Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes - distributed by Hal Leonard Corporation

Tonality: The song remains in G major for the first four stanzas before modulating to E major for the last stanza. Mark Carlisle believes Finzi wanted to clearly delineate the speakers "shift of perspective from one describing his beloved's actions in the first four stanzas to his own in the fifth and final stanza." (Carlisle, 144-5) Another curiosity with regards to tonal center in this song and many of Finzi's songs discussed in this site, is his penchant for obscuring the tonal center by simply refraining to use the leading tone. Dr. Carl Rogers created a table listing each pitch used in this song, with regards to the vocal line and in doing so discovered that Finzi doesn't use the leading tone in the first and third stanzas. Furthermore he discovered that when the leading tone is used in the other stanzas it falls on weak beats and never exceeds the length of an eighth note. (Rogers, 47-8) To see Dr. Rogers' table and his remarks about the song please refer to: Tonality - Rogers. For additional comments about the tonal center please refer to: Tonality - Van der Watt.

Transposition: Currently unavailable

Duration: Approximately three minutes and forty-seven seconds.

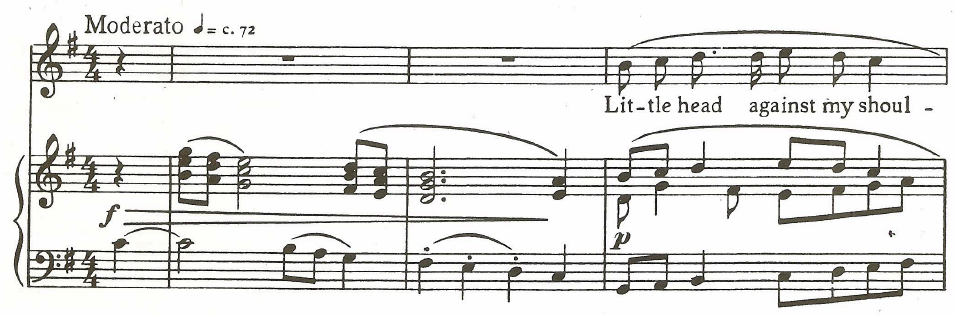

Meter: The song is in 4/4 meter throughout. For additional information please refer to: Metre - Van der Watt.

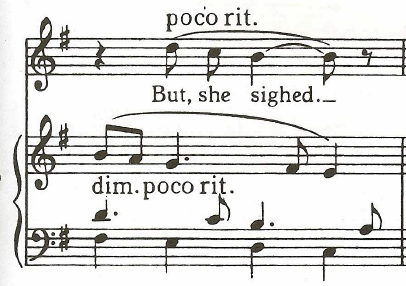

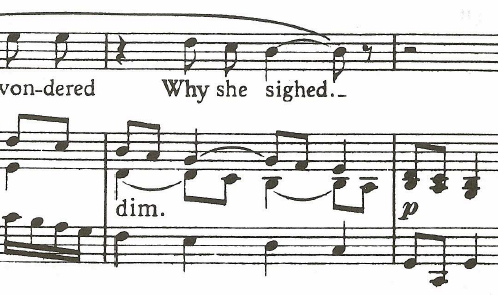

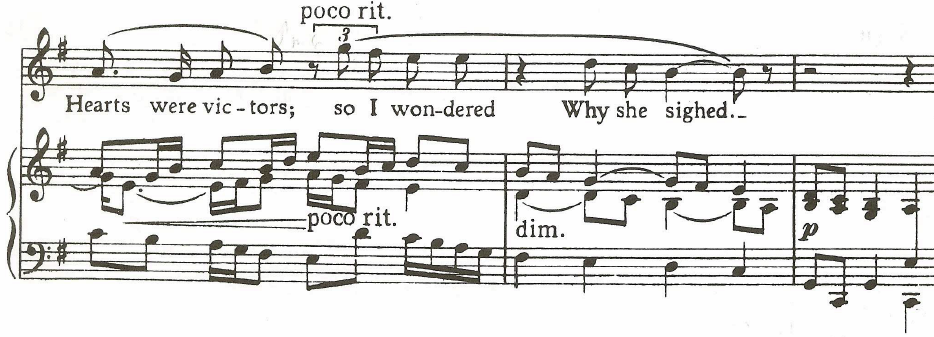

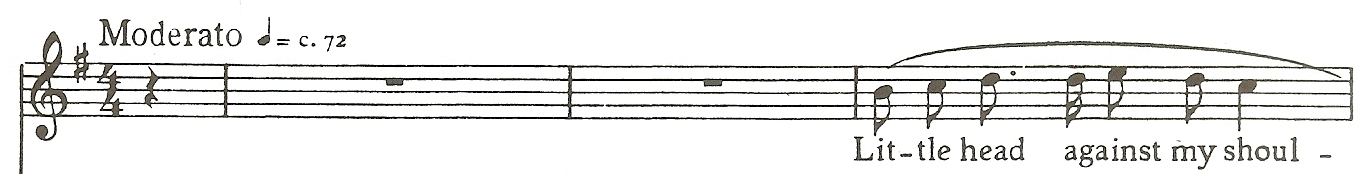

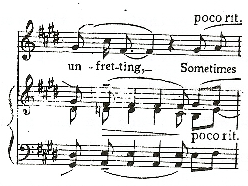

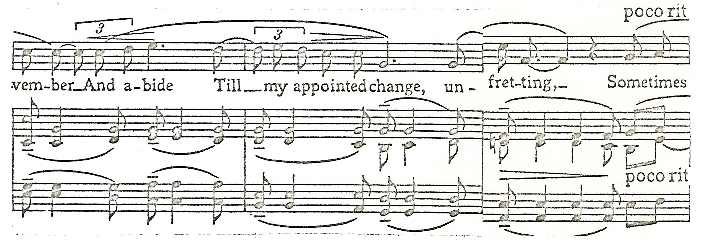

Tempo: Moderato with the quarter note equalling c. 72 is indicated at the beginning of the song. A poco ritard is indicated at the end of the first stanza before returning to the original tempo to begin the second stanza. Finzi uses a ritard on each subsequent stanza in preparation of the text where the speaker questions "why she sighed." There is one additional deviation from the opening tempo and it begins the last stanza where the indication is a tempo tranquillo. For further discussion about the tempi please refer to: Speed - Van der Watt.

Form: The form of the song can be described as A B A¹ B¹ C. The first two stanzas and the third and fourth stanzas could also be described as modified strophic with the last stanza as a coda. For additional comments about the specific sections of the song and other information about the form please refer to: Structure - Van der Watt and Form - Carlisle.

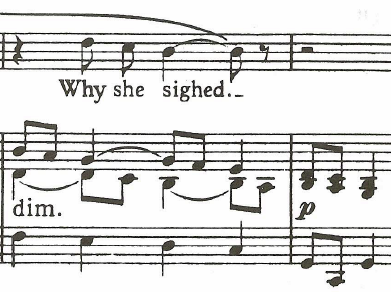

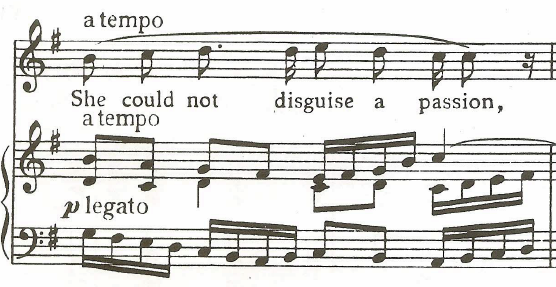

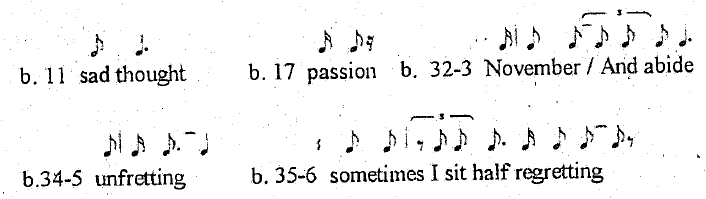

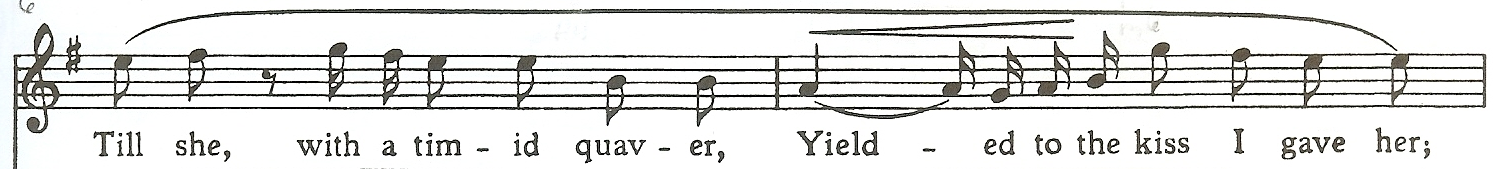

Rhythm: A rhythmic motif that is prevalent throughout the song is first heard in the piano accompaniment in measure one and consists of two eighths followed by a longer note value (see example below). The first occurrences in the piano accompaniment also involves imitation between the right and left hands. Please note also there are several variations for the longer note value in these examples.

Rhythmic motif as found in piano accompaniment and vocal line at the beginning of the song. (Finzi, 154)

In these first examples of the rhythmic motif the imitation could be described as playful but when the vocal line takes over the motif becomes more firmly established. Note also how the outer voices of the piano parallel the vocal line to begin the song, thus adding strength to the motif. When the vocal line enters It is also the first time the motif has an ascending melodic pattern.

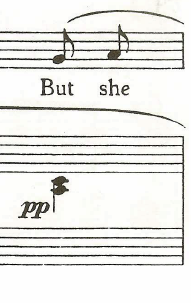

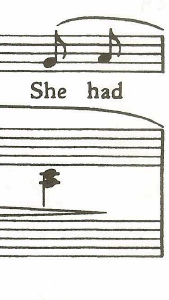

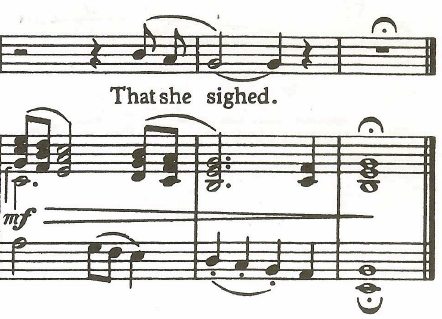

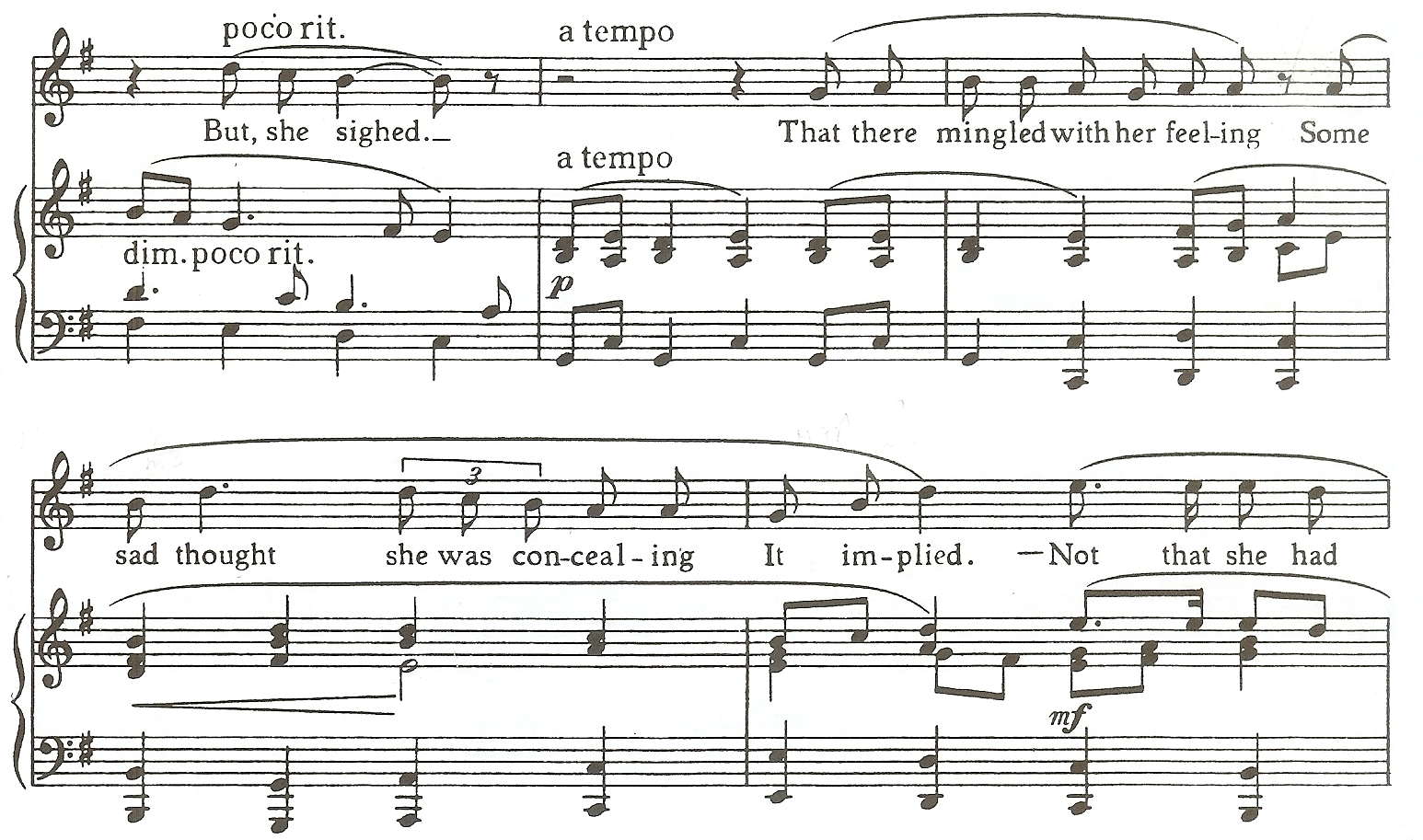

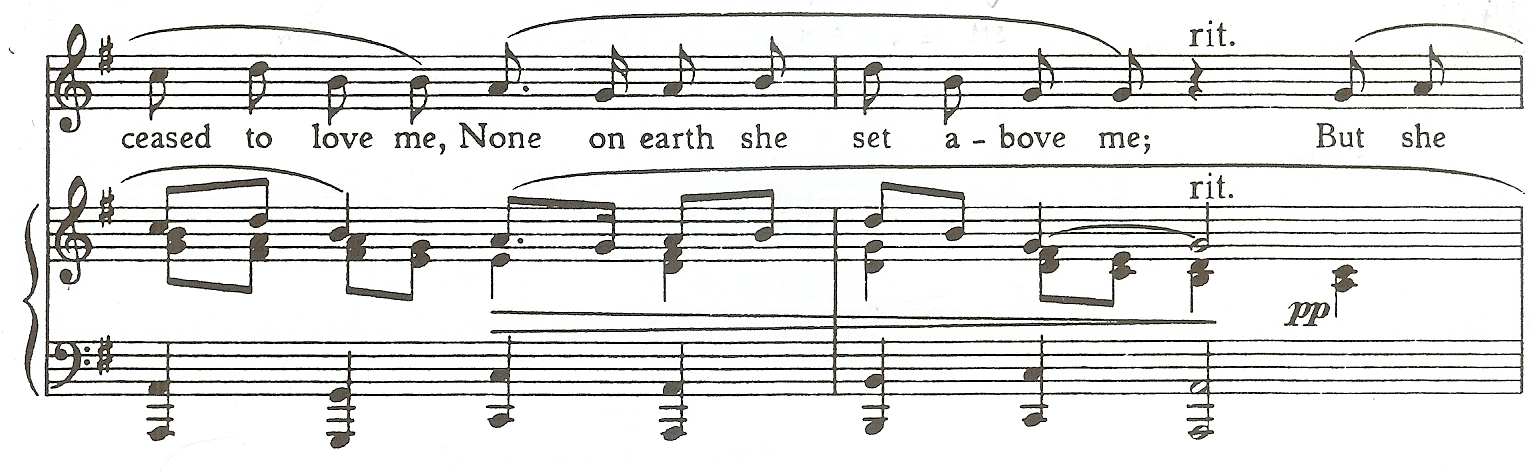

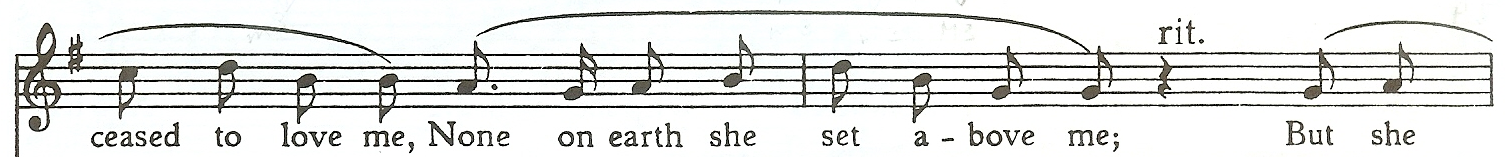

This same rhythmic motif also serves to unify the song throughout in that it is always used to conclude each stanza of the poem in the vocal line (see examples below).

Rhythmic motif, found in measure 8, used to conclude first stanza. (Finzi, 155)

Rhythmic motif, found in measures 14-5, used to conclude second stanza and then echoed in piano. (Finzi, 155)

Rhythmic motif, found in measures 22-3, used to conclude third stanza and again echoed in piano. (Finzi 156)

Rhythmic motif, found in measures 28-9, used to conclude fourth stanza and echoed in piano. (Finzi, 157)

Rhythmic motif, found in measures 37-8, used to conclude fifth or final stanza. (Finzi, 157)

In the examples above it should also be pointed out there are numerous melodic variations that accompany the rhythmic motif. It should also be noted that because the motif is so prevalent in the song that many times it may go unnoticed but even when these occurrences happen the motif unifies the song at possibly the subliminal level.

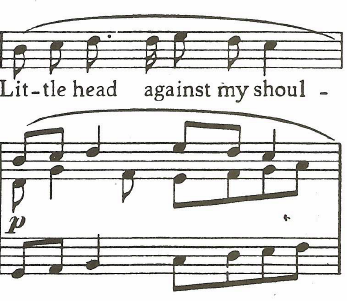

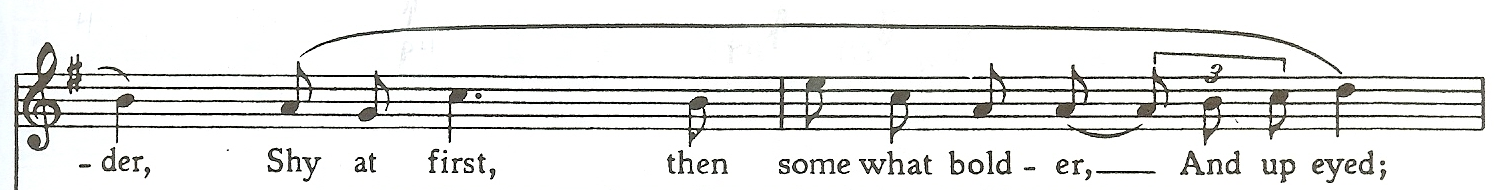

Beyond the motif mentioned above the song displays Finzi typical use of rhythm as well as his skill at text setting that is mentioned several times throughout the analysis pages of this site. This song has more text than many of the songs in the song set, A Young Man's Exhortation, nevertheless Finzi's creativity with rhythms makes each verse unique, albeit a subtle one. For example, there is a very subtle change in the opening of the first stanza and the third as one might expect in a modified strophic song but Finzi's subtle rhythmic changes in order to accommodate the text is quite satisfying and probably would go unnoticed by most who listen to the song. Please note the rhythmic change from "shoulder" in the first stanza to "passion" in the third stanza (see example below).

Beginning of 1st stanza, measure 3. (Finzi, 154)

Beginning of 3rd stanza, measure 17. (Finzi, 156)

In both examples above it should be noted that the piano accompaniment is very different and so even though there is a subtle difference in the rhythm of the vocal line it is somewhat overshadowed by the contrasting piano accompaniment. An example of a slightly unusual rhythm for Finzi occurs in the interlude between the second and third stanzas (see example below).

Curious rhythm in bass line of interlude between 2nd and 3rd stanzas, measure 15. (Finzi, 155)

Please note also how the rhythmic pulse is somewhat obscured with the inclusion of this rhythm on the third and fourth beats. The rhythm is also a bit curious because there are no other examples of it within the song. For additional comments about the rhythm and the rhythmic motifs of the song please refer to: Rhythm - Van der Watt.

A rhythmic duration analysis was performed and for the results please refer to: Rhythm Analysis. Information contained within the analysis includes: the number of occurrences a specific rhythmic duration was used; the phrase in which it occurred; the total number of occurrences in the entire song.

Melody: The most important melodic material within the song can be found accompanying the rhythmic motif that has been discussed at length above. A point that was mentioned above is the use of imitation and or echoing the conclusion of each stanza, there are also a few examples of the voice imitating the piano. An example of imitation by the voice can be found at the conclusion of the third stanza (see example below).

Imitation of accompaniment by vocal line, in measures 21-2. (Finzi, 156)

Note the imitation overlaps in the piano accompaniment and then the vocal line adopts the melodic pattern on the second beat of twenty-second measure. The imitation is concluded with the piano accompaniment in the twenty-third measure. Another curiosity about the use of imitation in the above example: it precedes the largest leap in the vocal line (see example below).

Large leap in vocal line in measure 21. (Finzi, 156)

Finzi typically reserves large leaps for text emphasis and this example seems to portray the frustration of the speaker at not understanding "why she sighed." For additional comments about the melodic material please refer to: Melody - Van der Watt.

An interval analysis was performed for the purpose of discovering the number of occurrences specific intervals were used and also to see the similarities if there were any between stanzas. Only intervals larger than a major second were accounted for in the interval analysis. For a complete description of the results of the interval analysis please see the table at the bottom of the page or click on: Interval Analysis.

Texture: The song is primarily homophonic with some contrapuntal writing. For a brief description about the texture including a table outlining the types of texture and the percentage in which they were used please refer to: Texture - Van der Watt.

Vocal Range: The vocal range spans an interval of a perfect twelfth. The lowest pitch is the D below middle C and the highest pitch is the G above middle C.

Tessitura: The tessitura spans the interval of a major sixth from the G below middle C to the E above middle C. A pitch analysis was performed for the purpose of accurately determining the tessitura and for the complete results please refer to: Pitch Analysis.

Dynamic Range: The dynamic range encompasses forte to pianissimo. The loudest dynamic indication occurs at the very beginning of the song in the piano accompaniment but by the time the voice enters the dynamic is piano. The majority of the dynamic indications are for the piano accompaniment but there are a few crescendo and decrescendo marks for the voice. The indications for the voice seem intuitive as they follow ascending melodic material for the crescendo and a descending melody for the decrescendo. Additional comments about the dynamics including a table are available at: Dynamics - Van der Watt.

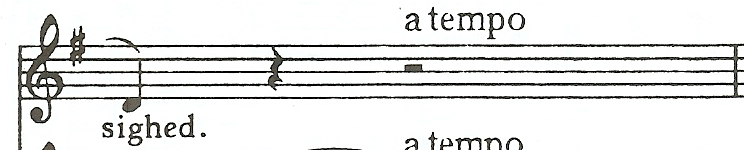

Accompaniment: The accompaniment is much more active in the third and fourth stanzas of the song, this is perhaps an attempt by Finzi to obscure his strophic writing for the vocal line nevertheless the middle of the song is certainly more active and more difficult to play than the beginning or the end. The song has a number of slight tempi changes throughout that need to be observed carefully in performance so as to not let the song get progressively slower. For additional comments about the accompaniment please refer to: Accompaniment - Van der Watt.

Pedagogical Considerations for Voice Students and Instructors: The range of this song is quite good for the tenor voice. There are two short sections, measures six through seven and measures twenty and twenty-one, however that may cause some difficulty with regards to the tessitura. One need be careful to not "act" with the voice in this song, a general mood of timidity could translate in to anemic support and a high larynx if one attempts to color the tone timid. Good breath management will be key to fixing either of these problems listed above. The breath at the end of measure five needs to be especially good in order to secure the requisite support for the upcoming phrase. The eighth rest between the text "she" and "with" should be an internal rest and one should be careful to not allow the chest to fall. In measure seven the leap to the high [G] from the [B] below middle [C] is very good. The sixteenth notes leading to the leap are also good for the voice. If one feels tight in the throat on the word "kiss" modify the vowel slightly by allowing additional space between the tongue and the roof of the mouth. One should also monitor the tendency to spread on this particular word. The difficulty in measure twenty could have its roots beginning in measure nineteen where the previous phrase begins to ascend in to the lower passaggio. When practicing this section one should begin in measure eighteen and carefully monitor the breath flow leading up to the [G] in measure twenty. A light articulation on the [N] consonant of "nothing" should help if one is experiencing a feeling of back pressure for the high [G]. Measure twenty-one is similar to the leap in measure seven except for the "rest" at the beginning of the triplet. If the [G] is tight when landed try elongating the [s] in front of "so." If the support is lacking substitute a [B] consonant for the [S] temporarily.

Dr. Mark Carlisle records in his dissertation the following observations and advice: "There are comparatively few specific performance considerations to address in a song of this nature, but some suggestions are warranted. The opening tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 72 is excellent, one of the most musically satisfying in all of these songs. It allows for a gently flowing motion to the music while at the same time permitting unforced and generally unhurried enunciation of the text. This tempo should remain in effect throughout both the A and A¹ sections, adjusting only for momentary expressive needs. However, a change should occur in measure 31 at the beginning of the coda, even though an a tempo is indicated. This section, marked tranquillo at the beginning, can be made more expressive and distinctive through the use of a tempo approximating [quarter note] = c. 52-56. The poet makes reference in this final stanza to his nearing the final years of his life, and the partial regret he continues to feel about "the sigh," so the tempo change will permit this last section to assume an interpretive weight somewhat deeper than those before it." (Carlisle, 149)

"The few dynamic markings found throughout the song in the accompaniment are all appropriate, and both singer and accompanist should make every attempt to observe them. It would be rather easy for performers to lapse into monotonous, unchanging dynamic gradations, but this would seriously diminish the quality of a song with little else that can provide substantial musical variety and interest. Wide dynamic contrasts are certainly not expected or required, but some variance is essential. "The introverted or extroverted nature of the text at any given moment provides the most serious impetus for dynamic change in this song, but this can and should be flexible based on the interpretive needs of the singer. The only specific dynamic suggestions are the following: 1) both singer and accompanist should diminuendo slightly at each return of the phrase "But, she sighed" in order to emphasize its importance, though not so much that the passage sounds unduly affected and unnatural; 2) both performers should pay particular attention to the pianissimo in measure 31. It provides a further means of differentiating this final section from its predecessors, as well as placing it in an appropriate "musical light." (Carlisle, 150)

"Beyond these basic factors, the only other interpretive aspect to consider is that of appropriate text stressing. While this is always of importance in any Finzi song, it assumes added significance in this piece due to the "enjambed" nature of the text. This enjambment can be seen in numerous places throughout the song, but some specific examples include measures 5-6, 11-12, and 25-26. These places and other of a similar nature require the singer to interpret textually rather than metrically, a factor quite common in the songs of Finzi, but especially important if a genuinely artistic performance is to be achieved." (Carlisle, 150-1)

"The technical and musical difficulties of this song are very few, and the text is certainly not among the more philosophically demanding of Hardy's poems. The tessitura of measures 6-7 and 20-21 may be a slight problem for a very young tenor, but since the piece is well-suited to a lyric voice, compromises can be made in dynamics and timbre that would not in any serious way diminish the quality of the performance. Certainly the singer should possess very good, flexible diction skills, as the analysis of this song has made clear, but this is not an uncommon trait in many young singers. Hardy's text, though by no means difficult by his standards, may still pose problems for an average first or second year undergraduate student. However, a third year tenor or beyond should inmost cases have the requisite capabilities of presenting a fine performance of this song. While it does not have strong or profound musical qualities, it can nevertheless be often used quite well to add a sense of "comfortable" variety to the middle of a vocal set." (Carlisle, 151)

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Below one will find excerpts from unpublished dissertations. The excerpts should provide a more complete analysis of The Sigh for those wishing to see additional detail. Please click on the link or scroll down.

Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt - The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

Michael R. Bray - An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

Audio Recordings

Songs

|

|

|

|

The Songs of Gerald Finzi to Words by Thomas Hardy

|

|

|

|

Gerald Finzi Song Collections |

|

|

|

The English Song Series - 16 |

|

|

|

Song Cycles for Tenor & Piano by Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

Songs by Britten, Finzi & Tippett |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Songs of the Heart: Song Cycles of Gerald Finzi |

|

|

|

✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦✼✦

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by Gerhardus Daniël Van der Watt. Dr. Van der Watt extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on October 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated November 1996, is entitled:

The Songs of Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) To Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt comes from Volume II and begins on page one hundred twenty-six and concludes on page one hundred twenty-seven. To view the methodology used within Dr. Van der Watt's dissertation please refer to: Methodology - Van der Watt.

1. Poet

Specific background concerning poem:

"The poem comes from Time's Laughingstocks (1909) and is undated. Martin Seymour-Smith suggests the following concerning the poem:"

(Van der Watt, 126)

"This could be a recollection of Emma, but it is more likely to be related to his experience with Florence [Dugdale, later his second wife], who might have sighed for Hyatt [a former suitor], or just out of self-pity from which she habitually suffered. The poem within its brief compass, seems to condense the whole experience: Such are the illusions of love, which changes rapidly." (Seymour-Smith, 719) (Van der Watt, 126) |

2. Poem

"A beloved sighs at the poet's kissing her for the first time. The poet, now approaching the end of his life, wonders in retrospect why his beloved sighed on that particular occasion: What sadness was she concealing? What passion was troubling her? The lovers stayed together, married and loved each well, yet she never confessed why she sighed. Now, in old age (awaiting death unconcerned) with her already gone, the poet mildly regrets that she sighed. He is unable to forget this one sigh and this makes him regret that he did not resolve the matter while his beloved was still alive."

(Van der Watt, 127)

"The poem is a love lyric with an undercurrent of regret."

(Van der Watt, 127)

"The poem consists of five sestets with a shortened third and sixth line in each stanza. The rhyme scheme is aabccb ddbeeb etc. The shortened lines rhyme throughout and the final line of each stanza becomes a varied refrain. The metre is mainly trochaic with some minor variation."

(Van der Watt, 127)

"The poem is a very honest statement by a poet, honest about his feelings even the painful ones of regret. It is a precise observation of the reality of love and self-searching in an attempt to understand. Seymour-Smith sums up Hardy's fairly frequent dilemma, specifically here about his affair with Florence Dugdale: "Tom was an honest man caught up in affairs in which he was no expert"."

(Seymour Smith, 718)

(Van der Watt, 127)

Setting

1. Timbre

VOICE TYPE/RANGE

"The song is set for tenor voice and the range is a perfect eleventh from the first D below middle C."

(Van der Watt, 127)

"The middle range of the piano is favoured in the piano accompaniment. The highest pitch employed is the second G above middle C and the lowest pitch the third G below middle C. The second and fourth stanzas use a lower sonority while the accompaniment of the other stanzas stays within the grand stave, exploring only the standard sonority of the piano. There are no indications for the use of the pedal. The largely legato touch indication (legato slurs, b. 17 legato) will necessitate the use of the pedal at the performer's discretion. Other indications of articulation are sparsely used. Mezzo-staccato indications are used in bars 2, 27, 28 and 38. In all cases the left hand pitches are separated from one another for the sake of mild emphasis. Portamento accents are localized to the last stanza (b. 33-35) where the first and third beats are slightly emphasized. This emphasis, with a new rhythmic motif and a slower tempo, accompanies the text: "I near November / And abide / till my appointed change, unfretting"."

(Van der Watt, 127-8)

"The atmosphere of the song is calm, somewhat resigned, retrospective, a little disillusioned and regretful. It stays fairly uniform throughout but becomes just slightly agitated in the second stanza (b. 16-21) with the text, "She could not disguise a passion" due to the more active rhythmic material. There is also an intensification of the original mood in the last stanza (b. 31 tranquillo) largely due to the slower tempo and key change to the lower minor third, E major. The atmosphere rests strongly on the sighing-motif (b. 1-2, 8, 22, 37-38) with a strong downward trend, decreasing in volume."

(Van der Watt, 128)

2. Duration

"The trochaic metre of the text is appropriately matched with a common-time time-signature. There are no deviations from this."

(Van der Watt, 128)

Rhythmic motifs

"The motif which occurs most consistently (62 times in both piano and vocal parts) throughout the song (motif 1) is derived from the text, "But she sighed" and consists of two quavers and a minim or crotchet. This motif opens and closes the song and the descending form is largely responsible for creating the resigned, somewhat regretful atmosphere. Motif 2 is localized to the second stanza, consists of four semi-quavers and occurs almost exclusively in the piano part (23 times). This motif, more active than the rhythmic material of the rest of the song, accompanies the idea of agitation related to the beloved's unconfessed, "passion", possibly "Dread or doubt" or even love for another, the persona's fear which he is not prepared to pronounce. Motif 3, consisting of a dotted quaver and a semi-quaver occurs 19 times in both piano and vocal parts (b. 3, 12(2), 13(2), 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 25, 26(2), 27(2), 31, 32, 36). The motif came into existence in order to accommodate the textual metre. Motif 4 (four crotchets) occurs 16 times only in the piano part and mostly in the bass often providing the harmonic rhythm (with the exception of stanza 2 (b. 17-21) where the harmonic rhythm is a quaver). The final motif for discussion (motif 5) occurs almost exclusively in the piano part and is localized in the final stanza. The quaver-crotchet-quaver construction embodies a rhythmic hesitation which is appropriately used with the text: "I near November / And abide / till my appointed change, unfretting". The persona, thinking back over many hears, is not sure that he wants to remember, yet he does and what he remembers, he half regrets."

(Van der Watt, 128)

Rhythmic activity vs. Rhythmic stagnation

"Stanzas 1, 2 and 4 are even and similar in their rhythmic movement. In the second stanza (b. 16-21) the piano part is slightly more rhythmically active, representing the agitation as mentioned before. The final stanza with its slower tempo, has a slightly less active rhythmic construction than the rest of the song, resulting in a hesitant, resigned atmosphere."

(Van der Watt, 128)

Rhythmically perceptive, erroneous and interesting settings

"The following words or phrases have been set to music perceptively:"

(Van der Watt, 129)

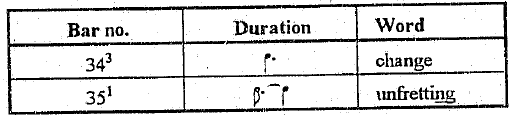

(Van der Watt, 129)

Lengthening of voiced consonants

"The following words containing voiced consonants have been rhythmically prolonged in order to make the word more singable:"

(Van der Watt, 129)

"The tempo indication is Moderato [quarter note equals] c. 72. Tempo deviations are listed below:"

Bar no. |

Deviation |

Bar no. |

Return |

Suggested reason/s |

8 |

poco rit. |

9 |

a tempo |

End of stanza 1 |

14 |

rit. |

15 |

a tempo |

End of stanza 2 |

16 |

rit. |

17 |

a tempo |

Anticipate start of stanza 3 |

21 |

poco rit. |

23 |

a tempo |

End of stanza 3, anticipate start of stanza 4 |

30 |

rit. |

31 |

a tempo, tranquillo |

Start of final stanza |

35 |

poco rit. |

Anticipate the end, dramatic hesitation |

3. Pitch

Intervals: Distance distribution

Interval |

Upwards |

Downwards |

Unison |

(38) |

|

Second |

52 |

57 |

Third |

10 |

10 |

Fourth |

6 |

3 |

Fifth |

0 |

4 |

Sixth |

2 |

0 |

"There are 38 repeated pitches (or 21% of the total number), 70 rising intervals (or 38%) and 74 falling intervals (or 41%). The smaller intervals (a third and smaller) account for 167 intervals (92% of the total number) while the larger intervals (fourths and larger) account for 15 (or 8%). The vocally descending trend is slightly mor prominent than the ascending one. This can be attributed to the number of times that the sighing-motif appears. The setting is vocally very sympathetic and no leap larger than a sixth is used."

(Van der Watt, 129-30)

Interval |

Bar no. |

Word/s |

Reason/s |

4th up |

4 |

at first |

Emphasis |

4th up |

4-5 |

then some |

Emphasis |

4th down |

6 |

timid quaver |

Reinforce emotional content |

6th up |

7 |

the kiss |

Emphasis |

5th down |

14-15, 28-29 |

she sighed had sighed |

Reinforce emotional content |

4th up |

18 |

or doubt |

Emphasis |

6th up |

21 |

victors so |

Emphasis |

5th down |

31 |

remember |

Reinforce emotional content |

4th down |

34 |

appointed change |

Reinforce emotional content |

5th down |

35 |

unfretting |

Reinforce emotional content |

Melodic curve

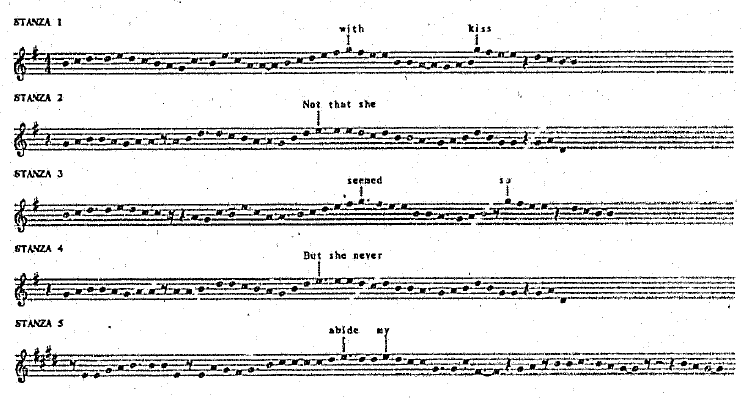

"A melodic curve of the vocal line is represented below. Certain words are indicated to show the relationship between the melodic curve and the meaning:"

(Van der Watt, 130)

(Van der Watt, 130)

Climaxes

"The vocal climaxes are given below:"

Bar no. |

Pitch |

Word |

6 |

G |

with |

7 |

G |

kiss |

20 |

G |

second |

21 |

G |

so |

33 |

E |

abide (E major) |

34 |

E |

my (E major) |

Phrase lengths

"Phrases correspond to the stanzas (b. 3-8, 9⁴-15, 17-22, 23⁴-29, 31-38) and ample place for breathing is allowed through rests. There is, however, one point in each stanza where it will be necessary to take a breath: bars 4⁴, 12², 19⁴, 26², and 33⁴."

(Van der Watt, 131)

"The song is set in G major with a single modulation just before the final stanza to E major. The modulation is abrupt and places the last stanza in a lower register, appropriate to the retrospective view taken here."

(Van der Watt, 131)

"There is a single instance of chromaticism on bar 35¹ where the leading note of E major has been lowered. The result is a lowered chord vii₉ (D-F#-A-C#-E). The D natural can also be seen as a sustained chromatic passing note between D# and C# in which case the chord is really ii⁶₅. More important, however, is the fact that this single chromatically altered chord occurs on the word, "unfretting". The implication seems to be that the composer belies the assertion of the poet that he is unfretting by lowering the leading note."

(Van der Watt, 131)

HARMONY AND COUNTERPOINT

"The use of first inversion chords is an important part of the general harmonic language. A number of strings consisting of first inversion chords will serve as examples: bars 5¹ - 6¹, 8¹-⁴, 22¹-⁴. A strong relationship is established between chords I and ii or ii (b. 1³-⁴, 2³-⁴, 3¹-², 4¹-², 7³-⁴, 9¹-10², 11²-³, 12⁴-13¹, 14³-15¹, 15³-16¹, 17³-⁴, 18¹-², 21³, 22⁴-24², 25²-³, 29³-30¹, 35³-36¹, 37³-⁴, 38⁴-39¹), often in cadential positions resulting in a plagal cadence of sorts."

(Van der Watt, 131)

Non-harmonic tones

"Non-harmonic tones included a multitude of suspensions, passing notes (accented and unaccented) and appoggiaturas, none of which are outside the composer's normal, abundant use of non-harmonic tones."

(Van der Watt, 131)

Harmonic devices

"There are no significant pedal points used. The chord vii₉ used on bar 35¹, can alternatively be seen as the stacking of two triads with a common note between them: A-C#-E (V) and D-F#-A (vii lowered). The effect of this dissonance has already been discussed.

(Van der Watt, 131)

Counterpoint

"A lot of free counterpoint characterizes the general material of the song. There are a number of cross-references between piano and voice in the form of brief imitations. These help to ensure a close relationship between piano and voice:"

8¹-² piano - 8²-³ voice |

|

14⁴-15¹ voice - 15²-³ piano |

|

21⁴-22¹ piano - 22²-³ voice |

|

28⁴-29¹ voice - 29²-³ piano |

|

37¹-² piano - 37⁴-37¹ voice |

"There are also a number of internal imitations in the piano part: bars 1, 22-23, and 37."

(Van der Watt, 131)

"Loudness variation is given in the following summary:"

(Van der Watt, 132)

FREQUENCY

"There are 34 indications in the 39 bars only three of which are in the vocal part. The vocal part should follow the indications given in the piano part where there are no separate indications."

(Van der Watt, 132)

RANGE

"The highest level indicated, f is found on the single upbeat note (b. 0⁴) and is repeated. The significance is that it establishes the decreasing dynamic level with the descending melodic trend of the sighing-motif. The lowest indicated level is pp and occurs in bars 14 with the text, "But she sighed" and 31 and the start of the final stanza with the text, "It was in our May". "

(Van der Watt, 132)

VARIETY

"The indications used are:"

(Van der Watt, 132)

DYNAMIC ACCENTS

"The only indications are the portamento accents in bars 33 - 35. These emphasize the first and third beat of each bar whereby the metre is almost altered to 2/4 for a short while. These mild accents have an unsettling effect, ironically, with the text: "In near November / And abide / Till my appointed change, unfretting,"."

(Van der Watt, 132)

"The density varies loosely between four and six parts including both piano and voice. The thickness of the piano part is represented in the following table:"

No. of parts |

No. of bars |

Percentage |

3 parts |

19 |

49 |

4 parts |

8 |

20 |

5 parts |

12 |

31 |

"The upbeat (b. 0⁴) consists of a single note and there are also portions of two other bars that consist of single note motifs (b. 16-⁴, 30-⁴). The latter both serve as linking passages to a new stanza. Stanzas 1 and 3 have a three-part texture. These differences in texture provide variety rather than being directly related to the meaning."

(Van der Watt, 133)

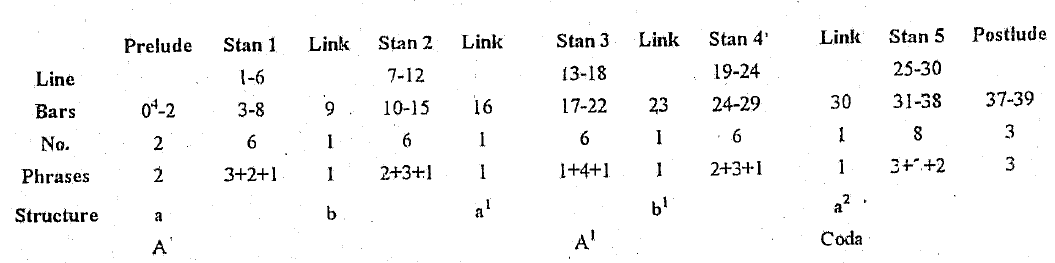

"The structure of the song is represented in the following table:"

(Van der Watt, 133)

(Van der Watt, 133) "The song is in the varied strophic form with alternate stanzas similar and the final on a more extensive variation on the original, serving as a coda."

(Van der Watt, 133)

7. Mood and atmosphere

"The mood of the song is contemplative, regretful, almost at peace, yet a little hesitant. The "passion", referred to in the text (l. 13) is set with more active rhythmic material in the accompaniment which results in an atmosphere of understated agitation. The change of key in the last stanza (b. 31) takes the register a minor third lower and softens the atmosphere in view of the reference to old age (l. 26 "I near November") and the mild regret the persona feels as a result of the beloved's sigh so many years ago. This regretful nostalgia is further enhanced by a slower tempo (b. 31 tranquillo and b. 35 poco rit.) and slightly slower rhythmic movement."

(Van der Watt, 133)

General comment on style

"The setting of the song is vocally very sympathetic (92% smaller intervals). The harmonic usage is characterized by a strong relationship between chord I and ii or ii₆ and an incessant addition of the seventh to the triad. There is a single chromatic alteration on the word "unfretting", which seems to indicate that the composer was not so sure that the persona was "unfretting". The style characteristic which is illuminated here is the composer's meticulous attention to detail in setting a text. There is an evenness of atmosphere with sensitive deviations like the slight agitation suggested in the third stanza (b. 17-21) and the intensified awareness of regret in the final stanza (b. 31-39)."

(Van der Watt, 133)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by Mark Carlisle. Dr. Carlisle extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 7th, 2010. His dissertation dated December 1991, is entitled:

Gerald Finzi: A performance Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation and

Till Earth Outwears, Two Works for High Voice and

Piano to Poems by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page one hundred forty-three and concludes on page one hundred fifty-one of the dissertation.

"This poem is part of a collection entitled Time's Laughingstocks that was published in 1909. It is further described by its inclusion in the grouping, "More Love Lyrics." The poem is not dated, and the woman discussed in its verses is unknown. Some have read regret and sadness into the poem, while others have found humor in it: "Throughout each stanza the perturbed lover reassures himself of her sincerity, only to return amusingly at each final line to the most delicate of doubts.""

(Bailey, 217)

(Carlisle, 143)

"The poem expresses a common sentiment of the day; that it is impossible to truly know the thoughts and feelings of another person, and that in the final analysis we each simply create our own reality of a given relationship. Hardy expressed the same attitude in Under the Greenwood Tree, where the character Fancy Day states: "Now, Dick, this is how a maid is. She'll swear she's dying for thee, and she will die for thee: but she'll fling a look over t'other shoulder at another young feller, though never leaving off dying for thee just the same.""

(Bailey, 217)

(Carlisle, 143)

Comments on the Music

"The gentle, introspective nature of this poem elicited from Finzi a similar musical approach; uncomplicated and without great drama, yet incorporating much refined sensitivity and expressiveness. It is not unusual or exceptional in any of the basic elements of music, but rather seeks simply and eloquently to communicate the delicacy and tenderness of the text without a great deal of musical interference. This piece does not represent song writing at its most artistically and dramatically inspiring, but is instead merely an honest and heartfelt rendering of a common, touching sentiment."

(Carlisle, 143-4)

"The piece is thirty-nine measures in length, and structured in primarily a varied-strophic format that concludes with a epilogue-like section for the final poetic stanza. Measures 1-16 constitute the first A section, measures 17-30 the second, and measures 31-39 the epilogue. The two main sections can be further divided into subsections corresponding to the following structure: A=a,b; A¹=a¹,b¹. The measure numbers for these subsections are as follows: a=measures 1-8; b=measures 9-16; a¹=measures 17-22; and b¹=measures 23-30. The epilogue, while distinctly different from the previous sections due to a change of key, interpretive markings, and length, still retains a clear melodic and textural connection to them, and is therefore best described as a c¹ subsection rather than a third A section."

(Carlisle, 144)

"The song opens with an upbeat in the left hand of the accompaniment followed by two full measures of a piano prelude before the voice enters in measure 3. This occurs within a time signature of 4/4 that remains the same throughout the song. There is no postlude, but measures 15-16 and 29-30 respectively serve as brief interludes before the following section. The opening key of G major remains intact until the beginning of the epilogue in measure 31, at which time occurs an abrupt and unprepared change to E major that remains unaltered to the end. This harmonic change corresponds to the poet's shift of perspective, describing the beloved's actions and thought throughout the first four stanzas, then his own in the fifth and final stanza."

(Carlisle, 144-5)

"There is throughout this song much use of the mild passing and neighboring dissonances, appoggiaturas, and soft suspensions so characteristic of Finzi, but they are used merely to embellish what is certainly one of the most harmonically consonant of all of his songs. The key change from G major to E major is quite literally the only harmonic change of any significance and interest in this piece, and even its importance would be mitigated were it not for an interpretive change that is desired at this point. Harmony is at times a most important factor in the structure of a Finzi song, but in this case its simplicity relegates it to a secondary role behind other more important aspects."

(Carlisle, 145)

"Neither the vocal melody nor texture are remarkable, but they are the elements most prominent in this piece. The slight changes in melodic structure and tessitura between stanzas are the primary means of division of the song into the previously discussed subsections, while a change in patterns and texture in the accompaniment in measures 16-17 also helps to further define the second A section. The melody itself is fundamentally simple and well-phrased, even given the necessity of elastic rhythms due to Finzi's penchant for accurate speech stresses. For example, the singer's opening bar must be perceived as a 5/4 measure in order to create accurate word stress."

(Carlisle, 145-6)

"This song is rooted not so much in the folk tradition but rather in the 18th-century style of English composing that incorporated basically uncomplex, tuneful diatonicism. Finzi does make use of a descending eighth-note pattern at each utterance of the words, 'But, she sighed,' which adds a light touch of text-painting at these moments, but the overall structure of the melody is most certainly designed for simplicity of textual delivery (see Example 18)."

(Carlisle, 146)

"Example 18. 'The Sigh,' measures 8-16." (Carlisle, 146-7) |

"Much the same could be said of rhythm. Finzi's choice of rhythms in any given piece is usually tied so closely to the text that the combined effect of both rhythm and word is often quite 'conversational,' and such is the case in this song. There are several instances, such as in measures 3-4, 12-13, and 26-28, when the melody is nearly doubled in the right hand of the accompaniment, and even when not, rhythms of the accompaniment still fall within the general framework of textual and melodic rhythms (see Example 18)."

(Carlisle, 147)

"Interest is maintained, however, through some slight changes from section to section that keep the aspect of rhythm from becoming overly monotonous. The first A section consists primarily of eighth-note, quarter-note movement that changes in section A¹ to a greater emphasis on embellishing sixteenth-note patterns, particularly in subsection a¹. The basic rhythmical structure of the epilogue is similar to that of section A, but is differentiated somewhat by the use of syncopation in the accompaniment in measures 33-35, a reflection of the syncopation found in measure 15. These changes are noticeable and important in adding variety and interest to the song as a whole, but at no time do they complicate or interfere with textual clarity."

(Carlisle, 147-8)

"The texture in this song is of average density in relationship to other Finzi songs, with the vast majority of chords containing only three notes until those in the coda. The A section consists of a mixture of polyphonic and homophonic elements quite typical of Finzi's writing, but the A¹ section assumes a much more contrapuntal nature, particularly in the first few measures. The embellishing sixteenth-note patterns in measures 17-21 move from hand to hand in the accompaniment, and even further, from 'voice to voice' in each hand, before returning to a chordal, hymn-like structure in measures 22 and particularly 23. Measures 33-35 of the coda, in syncopated rhythm, are of a strictly chordal style. The represent the most substantial change in texture since measure 17, but the remainder of this final section corresponds in textural style to that of section A. The aspect of texture, as well as that of melody and rhythm, changes enough to add a sense of variety and interest to the song, but never so much that it becomes a strong focal point for the listener. Finzi always wrote with an extraordinary affinity for the spoken word, particularly with respect to the importance of accurate word stress, but this song evidences that importance to a greater degree than many of his other songs. It does not offer the listener a profound relationship between words and music, but for those who seek a vocal piece free from excessive musical affectations, it can provide considerable pleasure for the few brief moments of its duration."

(Carlisle, 148-9)

Comments about Performance

"There are comparatively few specific performance considerations to address in a song of this nature, but some suggestions are warranted. The opening tempo marking of [quarter note] = c. 72 is excellent, one of the most musically satisfying in all of these songs. It allows for a gently flowing motion to the music while at the same time permitting unforced and generally unhurried enunciation of the text. This tempo should remain in effect throughout both the A and A¹ sections, adjusting only for momentary expressive needs. However, a change should occur in measure 31 at the beginning of the coda, even though an a tempo is indicated. This section, marked tranquillo at the beginning, can be made more expressive and distinctive through the use of a tempo approximating [quarter note] = c. 52-56. The poet makes reference in this final stanza to his nearing the final years of his life, and the partial regret he continues to feel about "the sigh," so the tempo change will permit this last section to assume an interpretive weight somewhat deeper than those before it."

(Carlisle, 149)

"The few dynamic markings found throughout the song in the accompaniment are all appropriate, and both singer and accompanist should make every attempt to observe them. It would be rather easy for performers to lapse into monotonous, unchanging dynamic gradations, but this would seriously diminish the quality of a song with little else that can provide substantial musical variety and interest. Wide dynamic contrasts are certainly not expected or required, but some variance is essential. "The introverted or extroverted nature of the text at any given moment provides the most serious impetus for dynamic change in this song, but this can and should be flexible based on the interpretive needs of the singer. The only specific dynamic suggestions are the following: 1) both singer and accompanist should diminuendo slightly at each return of the phrase "But, she sighed" in order to emphasize its importance, though not so much that the passage sounds unduly affected and unnatural; 2) both performers should pay particular attention to the pianissimo in measure 31. It provides a further means of differentiating this final section from its predecessors, as well as placing it in an appropriate "musical light."

(Carlisle, 150)

"Beyond these basic factors, the only other interpretive aspect to consider is that of appropriate text stressing. While this is always of importance in any Finzi song, it assumes added significance in this piece due to the "enjambed" nature of the text. This enjambment can be seen in numerous places throughout the song, but some specific examples include measures 5-6, 11-12, and 25-26. These places and other of a similar nature require the singer to interpret textually rather than metrically, a factor quite common in the songs of Finzi, but especially important if a genuinely artistic performance is to be achieved."

(Carlisle, 150-1)

"The technical and musical difficulties of this song are very few, and the text is certainly not among the more philosophically demanding of Hardy's poems. The tessitura of measures 6-7 and 20-21 may be a slight problem for a very young tenor, but since the piece is well-suited to a lyric voice, compromises can be made in dynamics and timbre that would not in any serious way diminish the quality of the performance. Certainly the singer should possess very good, flexible diction skills, as the analysis of this song has made clear, but this is not an uncommon trait in many young singers. Hardy's text, though by no means difficult by his standards, may still pose problems for an average first of second year undergraduate student. However, a third year tenor or beyond should inmost cases have the requisite capabilities of presenting a fine performance of this song. While it does not have strong or profound musical qualities, it can nevertheless be often used quite well to add a sense of "comfortable" variety to the middle of a vocal set."

(Carlisle, 151)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by Leslie Alan Denning. Dr. Denning extended permission to post this excerpt from his dissertation on September 8th, 2010. His dissertation dated May 1995, is entitled:

A Discussion and Analysis of Songs for the Tenor Voice Composed by Gerald Finzi with Texts by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page sixty-six and concludes on page sixty-seven of the dissertation.

"In Hardy's poem 'The Sigh' from his Time's Laughingstocks collection, we find a direct counterpart to 'Ditty' form Part I. Whereas the young lover extols his new found romance in Part I, 'The Sigh' describes his lover after her death. Our character relives and cherishes encounters throughout their relationship, yet wonders if the sigh after the first kiss indicated something he never knew. The poem reflects a remembrance of a shared love of life. Finzi responds appropriately with a setting that is also a direct counterpart to 'Ditty,' both in style and form. The ballad style is reminiscent again of the English composers of the eighteenth century, containing a diatonic melody which, like 'Ditty,' could well stand unaccompanied. Again the folk song influence shows in Finzi's incorporation of Vaughan-Williams' 'Linden Lea' melody. the structure is deceivingly simple in appearance, with neat phrases of irregular lengths and flexible rhythms which accommodate the varied stresses of the different stanzas of text. Examining the voice part of the first two stanzas provides adequate example of this (musical Example 12)."

(Denning, 66)

"Example 12: The Sigh, Measures 1-15, vocal line only." (Denning, 67) |

"A reference to the earlier description of 'Ditty' would suffice here with the exception of the last stanza. Here the text changes from the lovers' retelling of the incident to his present-day thoughts. At this point Finzi employs a most effective abrupt modulation from G-major to the submediant key of E-major."

(Denning, 67)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas Hardy

This excerpt begins on page forty-seven and concludes on page fifty-one of the thesis. (Rogers, 47-51)

Part II, Number 2

"The Sigh"

The general character of this song hinges on the observations that:

(a) The text setting is syllabic throughout.

(b) It is in the style of a folk song and is very quiet and serene in mood.

(c) It consists of five stanzas and its form is A B A¹ B¹ C.

The first four stanzas of "The Sigh" have a tonal center of G-major, with a key signature of one sharp. No notes other than those occurring in the diatonic scale of G major are found in the first four stanzas of the song, either in the piano accompaniment or the vocal line. Neither the second nor the fourth stanzas contains the leading tone, F-sharp, in the vocal line. A modulation occurs with the beginning of the fifth stanza. The tonal center for this fifth and final stanza is that of E-major, with a key signature of four sharps. The scale used by the composer in this song is of interest, since one scale degree, the seventh, is conspicuously neglected in the vocal line. Table VII shows the relative total duration of each of the scale tones in the melodic line of the entire song. The infrequent use of the seventh scale degree is particularly noticeable.

TABLE VII

EMPHASIS ON SCALE DEGREES OF "THE SIGH" BY DURATION

Scale Degree |

Number

of Beats |

|

3 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

28 1/6 |

5 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

19 |

2 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

18 1/4 |

6 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

13 2/3 |

1 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

13 5/12 |

4 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

12 11/12 |

7 |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

3 5/6 |

*[quarter note] = unit of the beat |

That this scale is related, as have been those of earlier songs, to the primitive English folk=song scales discussed by Cecil Sharp (see Table II, Table IV, or Table VI) is borne out by the following considerations:

(a) Two stanzas of the melodic line of the song do not contain the leading tone at all.

(b) In the remaining stanzas of the song in which the leading tone does occur in the melodic line, it never exceeds the value of an eighth note, and it always falls on an unaccented part of the beat.

(c) The total duration of the seventh scale degree is significantly less than the duration of each of the other scale degrees.

These characteristics place this scale, with its hesitating use of the seventh scale degree, in a classification already discussed in connection with earlier songs (see Figure 8); that is, the derivative six-note scale of pentatonic Mode I labeled by Cecil Sharp as "Hexatonic a."

Since this song is largely homophonic, there is little contrapuntal activity except that used in the third stanza. In this stanza, the text mentions love as being a "passion," and the accompaniment becomes much more agitated through the use of rather florid contrapuntal lines. This same device has been discussed in connection with earlier songs; for example, "A Young Man's Exhortation," and "Shortening Days." Here again, two upper voices of similar range and design in the piano accompaniment are supported by a relatively inactive bass line, as in the Baroque trio sonata. Figure 26 shows the use of this device in this song.

Fig. 26 -- "the Sigh," measures 19 and 20, contrapuntal activity in the piano accompaniment.

The composer's attention to the details of text setting can be seen in Figure 27 on the word "unfretting." The accented syllable of the word is extremely short. This syllable, "fret," which falls on the strong beat of the measure, is therefore given only a sixteenth note. The other two unaccented syllables of the word, although they each receive a longer note value, are not stressed, because they are unaccented.

Three other words similar to "unfretting" are found in the poetry of this song. The words are "fashion," "passion," and "regretting." The accented syllable in each word is similar in that it is very short. The setting of each of these three words is analogous to that of the example shown in Figure 27. Such a setting results in a speech-like rendering of each word.

Fig. 27 -- "The Sigh," measure 35, composer's setting of the word "unfretting."

The preceding was an analysis of The Sigh by Carl Stanton Rogers. Permission to post this excerpt was extended by Dr. Rogers' widow, Mrs. Carl Rogers on March 1st, 2011. Dr. Rogers' thesis dated August 1960, is entitled:

A Stylistic Analysis of A Young Man's Exhortation, Opus 14, by Gerald Finzi to words by Thomas HardyThis excerpt began on page forty-seven and concluded on page fifty-one of the thesis.

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by Michael R. Bray. Dr. Bray extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on March 19th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1975, is entitled:

An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

This excerpt begins on page forty-six and concludes on page fifty-one of the thesis.

(Bray, 46-51)

THE SIGH

|

||

|---|---|---|

LITTLE head against my shoulder, |

||

Shy at first, then somewhat bolder, |

||

|

||

Till she, with a timid quaver, |

||

Yielded to the kiss I gave her; |

||

|

||

That there mingled with her feeling |

||

Some sad thought she was concealing |

||

|

||

- Not that she had ceased to love me, |

||

None on earth she set above me; |

||

|

||

She could not disguise a passion, |

||

Dread, or doubt, in weakest fashion |

||

|

||

Nothing seemed to hold us sundered, |

||

Hearts were victors; so I wondered |

||

|

||

Afterwards I knew her throughly, |

||

And she loved me staunchly, truly, |

||

|

||

But she never made confession |

||

Why, at that first sweet concession, |

||

|

||

It was in our May, remember; |

||

And though now I near November, |

||

|

||

Till my appointed change, unfretting, |

||

Sometimes I sit half regretting |

||

|

||

"The Sigh" is a dainty love poem that has been variously analyzed. Even in the moment of yielding to the first kiss, the poem intimates that the woman was perhaps sighing in the thought of another lover. Hogan finds the poem humorous: "Throughout each stanza the perturbed lover reassures himself of her sincerity, only to return amusingly at each final line to the most delicate of doubts." (Hogan) Hardy expressed this same idea in Under the Greenwood Tree when Reuben says:

Now Dick, this is how a maid is. She'll swear she's dying for thee, and she will die for thee; but she'll fling a look over t'other shoulder at another young feller, though never leaving off dying for thee just the same. (Hardy, Chapter VIII)

One phrase, "Till my appointed change," echoes Job 14:14, ". . . all the days of my appointed time will I wait, till my change come." (Bailey, 217)

The woman he speaks of in the poem is undoubtedly his first wife Emma Gifford. When he speaks of May, November, and "she loved me staunchly truly / Till she died," he is referring to his first month-long visit with Emma in May, 1871 and her death on November 27, 1912. (Bailey, 13, 18)

"The Sigh" is divided into two parts. The first four verses constitute one section and are characterized by Hardy talking about the woman in the poem. The other section contains the last verse. It is characterized by an inward reflection and Hardy talking to the woman and about himself after her death. As might be expected, Finzi treats this reflected change of mood in a fashion like unto similar sections in previous songs.

The sigh itself is presented in the opening measures in the form of descending chords moving scalewise in a two eighth-half-note patterns. The bass line moves in "walking bass" fashion allowing for the very long and smooth phrasing seen in this song. The eighth-note motion remains constant in the right hand aiding the motion of the line. The melodic line flows quite easily rising and falling according to the demands of the text. A "quaver" in the accompaniment follows the word itself as alternating notes in alternating hands yield the unstable effect. Characteristically, Finzi ritards the end of the first verse. In fact, each of the first four verses are similar in that they all ritard into the phrase "But she sighed," and they all bring a return of the sighing theme in the accompaniment - descending motion towards the ritardando.

The first four verses have other common characteristics. They take the form ABAB not only in the melodic lines they contain, but also in the type of accompaniment they have. Verses one and three (A) are the uplifting verses straight forward in the message they present. The piano score is also straight forward and keeps the eighth-note (sixteenth-note motion in the third verse) motion constant. Verse two and four (B) both tender a more reflective almost melancholy feeling with the inclusion of sad thoughts and her death itself. The accompaniments are more static being composed of chorded quarter note motion and extensive use of the sighing theme in variation. The variation appears as thirds moving scalewise in ascending and descending motion often creating lush seventh chords. Suspensions abound within this movement most commonly at the ends of small phrases. All the phrases are very pliable and flexible lending to the fluctuation of the pondering, reassuring affirmations, and ironical disbelief. The unification in the song comes then, with the melodic form ABAB, the sighing motifs occurring throughout, the similarities of moods between the alternating verses, the cadential ritardandos, and the similarities in the verse interludes.

These interludes contain very subtle motions. After verses one and three, the interludes are rocking chords alternating back and forth. This reinforces the fluctuation that goes on in Hardy's mind as he ponders "why she sighed." After verses two and four, a single line interlude reduces any extraneous motion to a minimum allowing one to focus upon the forthcoming phrase. This is the effect produced as the interlude after the fourth verse eases the transition into the final section (verse five). (See Example 16)

The modulation to E Major in conjunction with composers "tranquillo" pianissimo directives, precipitate a

EXAMPLE 16A: "The Sigh" measures 30-31

marked change. While the text turns inwardly reflective, the voice begins in a quasi-recitative style intimating this change. The accompaniment bears a vague similarity to the opening syncopated rhythms in "Her Temple," as does the voice in the next measure. A truly effective setting of the phrase ". . . And abide Till my appointed change, unfretting" then follows. In echoing Hardy's beliefs of predestination

EXAMPLE 17: "The Sigh" measures 33-35.

in his life, Finzi employs a static chord structure centered around the pedal tone G. As Hardy abides "Till my appointed change," so too does the G wait to resolve. The chord progression vi-IV₇-I₇-IV₇-vi is filled with seventh chords and the unsettled minor six chord - all eager to resolve. The release unexpectedly surprises on with a IV+⁶/IV resolving to a IV+⁶.

The ending of "The Sigh" is a masterful piece of unification. The phrase "Sometimes I sit half regretting / That she sighed," is almost an exact duplicate of the opening measures and the phrase "Little head against my shoulder." The major difference is that the final phrase is backward in relation to the opening phrase. The final sigh then comes in descending fashion to veil the phrase in reminiscent wonder.

The preceding was an analysis of The Sigh by Michael R. Bray. Dr. Bray extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on March 19th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1975, is entitled:

An Analysis of Gerald Finzi's "A Young Man's Exhortation"

This excerpt began on page forty-six and concluded on page fifty-one of the thesis.

(Bray, 46-51)

Unpublished Analysis Excerpts

The following is an analysis of The Sigh by John Keston. Mr. Keston extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on September 30th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1981, is entitled:

Two Gentlemen from Wessex: The relationship of Thomas Hardy’s poetry to Gerald Finzi’s music.

This excerpt begins on page eighty-nine and concludes on page ninety-five of the thesis. To view Mr. Keston's Methodology please refer to: Methodology - Keston.

THE SIGH

|

||

|---|---|---|

LITTLE head against my shoulder, |

||

Shy at first, then somewhat bolder, |

||

|

||

Till she, with a timid quaver, |

||

Yielded to the kiss I gave her; |

||

|

||

That there mingled with her feeling |

||

Some sad thought she was concealing |

||

|

||

- Not that she had ceased to love me, |

||

None on earth she set above me; |

||

|

||

She could not disguise a passion, |

||

Dread, or doubt, in weakest fashion |

||

|

||

Nothing seemed to hold us sundered, |

||

Hearts were victors; so I wondered |

||

|

||

Afterwards I knew her throughly, |

||

And she loved me staunchly, truly, |

||

|

||

But she never made confession |

||

Why, at that first sweet concession, |

||

|

||

It was in our May, remember; |

||

And though now I near November, |

||

|

||

Till my appointed change, unfretting, |

||

Sometimes I sit half regretting |

||

|

||

POETIC METER

"The Sigh" is constructed of trochaic pulses. Lines one, two, four and five are rhyming tetrameter, having four feet, while lines three and six, also rhyming, have only one and one-half feet. Trochaic meter starts with a strong accent followed by a weak one.

RHYTHMIC RELATIONSHIP

Finzi, for the first time in the cycle, A Young Man's Exhortation, has kept a constant meter of four four time throughout the song. The natural rhythm of the words again dictates the values of notation and again Finzi uses syncopation, urging the performer to recite the musical adaptation of the poem as if it were being spoken. He uses much rhythmic variation thereby preventing metronomic syllabification. Dotted eighth notes and dotted quarters are used to stress important words like "head" in the first lines and "first" in the second line of the first stanza. With these devices and syncopation, Finzi puts syllabic and word stresses where they belong throughout the song.

TRANSLATION

No translation of the language is necessary for "The Sigh." The sentiments expressed unashamedly are easily understood.

WHY SHE SIGHED

In this poem Hardy seems to be concerned that although a kiss is reciprocated "she," because she sighs may be thinking of, or desiring another lover, not an uncommon sublimation. Considering Proust's statement that each of us creates and inhabits his own universe, it is therefore impossible to know, possess and unite with every individual one might admire or love from afar. (Bailey, 217) In spite of the doubt expressed at the end of each stanza, he is sure that she loves him. We do not know who she is specifically. Hardy seems to have had many spiritual involvements with pretty young women, sighing himself many times over them, yet never daring to tell except through his art. "Till may appointed change" (last stanza) referring to his end, appears in Job 14:14--"all the days of my appointed time will I wait till my change come." (Bailey, 217)

The preceding was an analysis of The Sigh by John Keston. Mr. Keston extended permission to post this excerpt from his thesis on September 30th, 2011. His thesis dated May 1981, is entitled:

Two Gentlemen from Wessex: The relationship of Thomas Hardy’s poetry to Gerald Finzi’s music.

This excerpt began on page eighty-nine and concluded on page ninety-five of the thesis.